Rolling Fork, Mississippi

At 15 people per square mile, Sharkey County the second most rural county in Mississippi and one of the most southern spots in the Mississippi Delta, nestled between Yazoo and Issaquena counties. The county remains both very agrarian and intensely wild, as it houses both the Delta National Forest, the only bottomland hardwood national forest in the US, and the Theodore Roosevelt National Wildlife Refuge Complex.

You’ve heard of Sharkey County even if you haven’t heard of Sharkey County. First, it’s said to be the birthplace of McKinley Morganfield (or Muddy Waters). Secondly, it’s why teddy bears exist.

In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt traveled to Sharkey County for a famed black bear hunt (Back in the day, Mississippi was home to black bears and panthers). Local-legend and bear-hunter-extraordinaire Holt Collier, a formerly enslaved man, was hired to help Roosevelt. Collier allegedly clubbed a 250-lb bear over the head with his rifle, knocking him out, lassoed him, and tied him to a tree, so Roosevelt could shoot it. Fortunately (IMO), Roosevelt ultimately couldn’t bring himself to shoot the animal, whether at Collier’s request or his own conscience. Regardless, the Teddy Bear was born.

And for the last twenty years, Sharkey County has hosted the Annual Great Bear Affair, a weekend of festivities. Each year, a chainsaw artist creates a new giant wood bear, which are scattered around Rolling Fork.

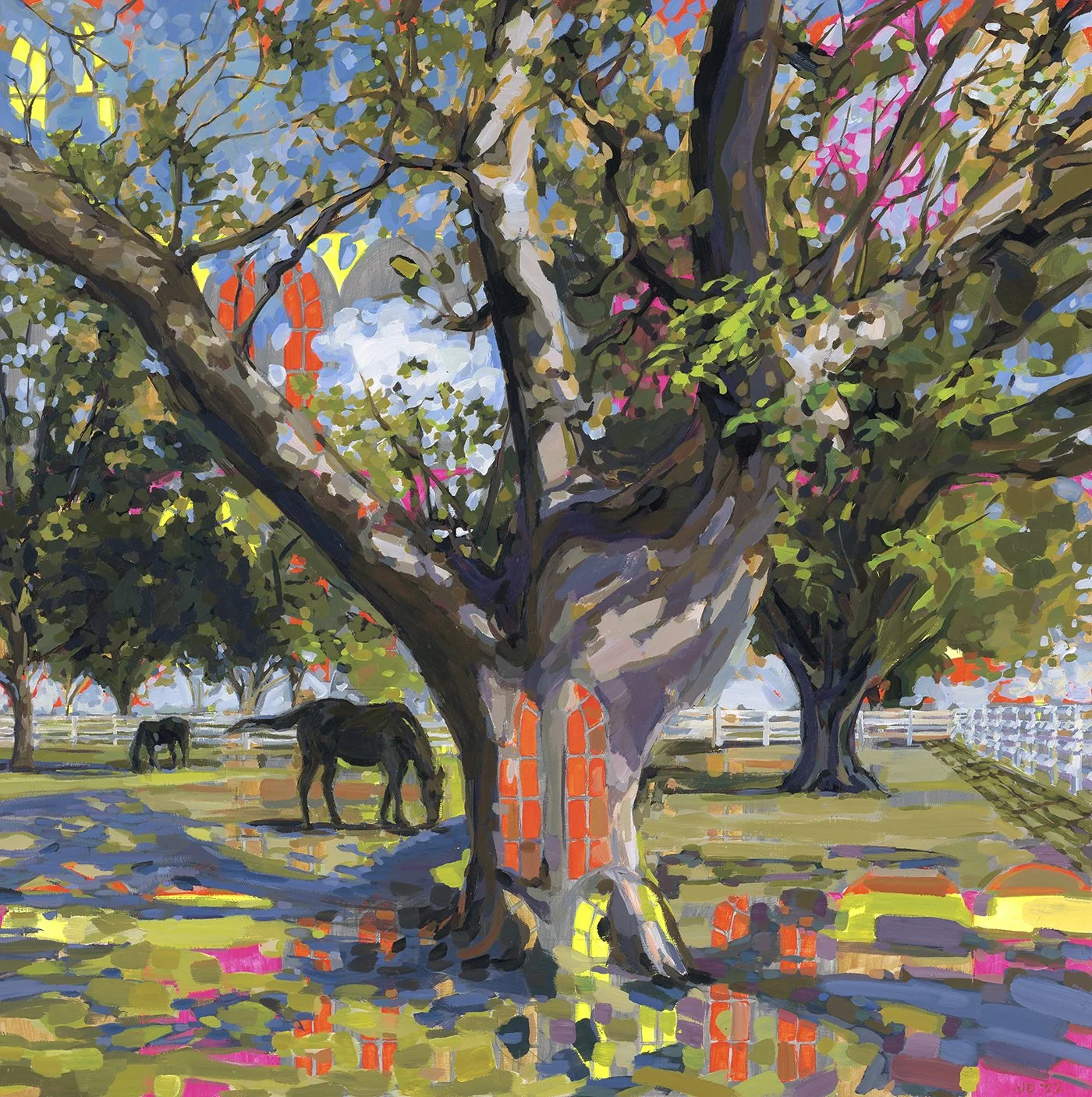

In early November 2019, I spent a lovely afternoon with Julia Rodgers and her father, Drick Rodgers, on their family farm outside of Rolling Fork in Sharkey County, Mississippi. I loved on horses, rode in a cotton picker, peeked into Mont Helena, and listened to remarkable family stories and histories.

Synthesizing folks and their places into short paragraphs and a couple of paintings barely skims the surface of each place I visit and each person I meet. I have found, however, that the common thread in these visits are the extraordinary/ordinary stories of care. And that care - care of land, of one another, of community, and of the animals that grace their lives - permeates each anecdote that Julia and Drick shared about living their lives in the Delta.

Born and raised in Rolling Fork, Julia left home briefly for college before returning in her early twenties to the family farm, which she helps to manage and where she currently lives with her husband and children. She has a handful of dogs and two, maybe three, handfuls of horses, many of which are geriatric or rescue, living out their golden years in her care. One horse she named Linda as a nod to Linda Blair’s performance in The Exorcist after Horse Linda literally flipped out in her stall after being weaned.

Julia’s also a competitive barrel racer, traveling throughout the south to ride in rodeos. Full disclaimer: I had no clue what barrel racing was until learning about Julia. And if you’re like me, here’s the deal: a person races a horse in a cloverleaf pattern around barrels as fast as possible. When a neighbor taught her to ride when she was a kid, Julia always only wanted to go fast. She rides most days, at least four times a week, and I caught her in between weekends trips to Louisiana to race.

More Than an Asset

Drick Rodgers, Julia’s father, equally awesome, comes from a long line of farmers. In 1920, his maternal grandfather moved to the area to serve in the first class of county extension agents after cooperative extension began. He bought 200 acres in Sharkey County shortly before the Depression, during which he had a dairy, and his wife, Drick’s grandmother, took in sewing to help make ends meet.

Both of Drick’s parents were farmers. His mother took over the farm after his father’s death, and I have no quantitative data to support this statement other than my gut, which I would bet was unusual for a woman to do during that time in the Mississippi Delta. Vivian Rodgers quickly began implementing conservation practices to address erosion, later served for a spell as the Soil & Water District Commissioner, and she was later awarded “Outstanding Farm Woman” by Staplcotn, the oldest cotton marketing cooperative in the nation. I’d like to pause here for a sec to let this all sink in. A woman took over a family farm in the Deep South in the 1970’s and made the farm more sustainable, which was assuredly not convenient and not fashionable at the time.

Drick has carried out this philosophy of ingrained care, twice winning Conservation Farmer of the Year by digging into forward-thinking conservation practices, and by restoring Mont Helena in the mid-1990’s. As Drick describes it, Mont Helena, built in the late 1890’s, was the retirement home of Helen Johnstone Harris, his great-great-great-great aunt’s sister and her Episcopal priest husband. The house, built atop a prehistoric Native American ceremonial mound, burned to the ground on move-in day. Undaunted, they rebuilt and lived there until their deaths in the early twentieth century. Following their deaths, the house remained empty, until Drick’s grandfather housed five or six families there, rent-free, during the Depression.

Like what you see? Invest in a painting or a print of Rolling Fork.