Greenwood, Mississippi

You can find Greenwood (pop. 13,600) in Leflore County, on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, where the Yalobusha and Tallahatchie Rivers form the Yazoo.

Both the county and the town were named after Greenwood Leflore, a Choctaw Chief in the 1820s who owned a cotton plantation and 32 enslaved people,and, after signing the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830, stuck around to serve in the state legislature. Leflore sided with the Union during the Civil War and was buried on his plantation, wrapped in an American flag.

Back to county-Leflore and town-Greenwood. In the early days of Reconstruction, the majority of Leflore County were African American tenant farmers raising cotton, many of whom were part of the 90,000 members of the Mississippi Colored Farmers’ Alliance, since they were excluded from the Southern Farmers' Alliance.

By the early twentieth century, Greenwood was nicknamed the "Cotton Capital of the World," and both the county and town were home to immigrant families from Syria, Palestine, Russia, Italy, Mexico, and Greece. On June 16, 1966, Civil Rights Activist Stokely Carmichael delivered his "Black Power" speech in Greenwood during a March Against Fear rally.

The next year began the successful, twenty-month Greenwood Movement boycott, a rare feat in Mississippi not only because of its length and breadth, but also from its multi-denominational support from the leaders of the Catholic St. Francis Center, the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The boycott eventually led to white business owners hiring Black employees, and to Black neighborhoods gaining paved streets and street lighting.

Greenwood is down the road from Mississippi Valley State University, one of the five HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities) in the state —the only one in the Delta— and where Jerry Rice got started.

In 1938, Robert Johnson, after selling his soul to the devil, was poisoned by a cuckolded juke joint operator (although his death certificate lists syphilis - not sure what's worse), and is allegedly buried in the cemetery of Little Zion Church in Greenwood.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Donna Tartt was born in Greenwood, and singer-songwriter Bobbie Gentry grew up there. Blues legend B.B. King was born in Leflore County before moving to Sunflower County as a kid.

Viking Ranges were born — and are still made — in Greenwood, the brainchild of Fred Carl Jr., who later endowed the Carl Small Town Center at Mississippi State University.

Viking remains the largest private employer in Greenwood, providing 600–650 local jobs and driving more than two decades of downtown revitalization.

I tell you all this because Context is Key.

It will make the stories behind the paintings that much more remarkable.

In 2019, I spent a day with Yolande Van Herdeen, an expat South African whose path serendipitously led her to Greenwood, Mississippi.

Incidentally, this isn’t all that unusual. For all the criticism Mississippi—and the Delta in particular—has received over the years, people often visit and then decide to stay. A short trip turns into a permanent move. Maybe it’s the sense that here they can make an impact, live more creatively, or take risks they wouldn’t elsewhere. Or maybe it’s simply the pull of the stories, the people, the music, and the food.

In Yolande’s case, her path to Mississippi ran through Los Angeles. In California, she befriended Martha Hall Foose—a Delta native, chef, and celebrated writer—and tagged along to Mississippi when Martha moved back east. What began as visits filled with good times gradually became something more lasting, until Yolande chose to make the Delta her home. After settling there, she met her husband, Scott Barretta, a blues writer and researcher, and the host of the Highway 61 Blues radio.

When I met her in 2019, Yolande was serving as the artist-in-residence at ArtPlace Mississippi, a community art center in downtown Greenwood offering classes and programs for all ages. What stayed with me from that visit wasn’t just the art itself, but the way Yolande explained the unique role ArtPlace plays in Greenwood.

Greenwood has 15 schools- public, private, religious. For a town of 13,600 people, that’s a lot. Each school has its own community with its own activities, sports and events. Add that to the dozens of churches in town, the many neighborhoods and private clubs, and it becomes clear why it can be such a real challenge to cross paths with people outside your own school, church, club, or neighborhood.

And so ArtPlace functions as a kind of bridge where youth from all schools, regardless of their art experience, can come and hang out and maybe get to know each other in the creative environment as well as teens in the teen art club (and the Grown Folks Art Club if you’re adult). In a town where cultures often run in parallel without ever crossing, places like this are rare. And they matter, deeply.

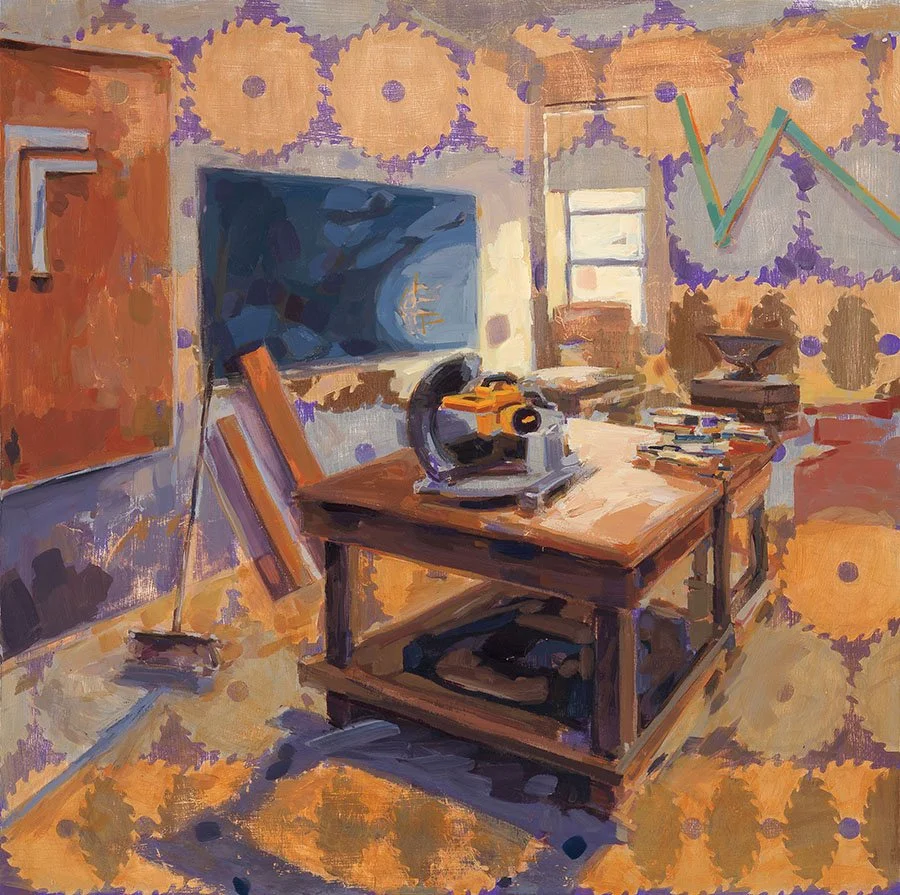

When I visited in 2019, Yolande walked me through the main teaching studios at ArtPlace, though we lingered longest in two—the woodshop and the quilt room. For me, they were a visual goldmine, overflowing with sparks for my paintings. But what really struck me was the programming she described taking place there: inventive, joyful, and the kind of hands-on learning I would have loved to experience back in middle school.

In 2019, ArtPlace Mississippi had a happening woodshop on the second floor of their downtown facility. If you’ve not spent much time in a woodshop, this one checked all the boxes: electrical saws and drills, a large wooden worktable, clamps, hand tools, spare lumber all covered with the fine mist of wood chips. Woodshops smell amazing, like fresh possibility and the forest.

In 2018 and 2019, this particular woodshop was outfitted at ArtPlace for Girls Garage workshops, which were held several times a year to teach women over 16 years basic building skills with power tools. Usually, 8 to 12 women would sign up and learn to build lamps or Christmas trees made from recycled wood or other inspired projects.

As they put it: ‘Greenwood’s Girls’ Garage is for ladies—both young and a little less young—to learn the basics of power tools, construction, and the confidence to take on projects of their own.’”

The Greenwood program was modeled after the original Girls’ Garage, founded in California in 2013 by an architect who set out to build confidence in young women and help close the gender gap in construction fields. Since then, more than 1,000 young women in California have taken part, completing 207 projects—including several that served their communities. The impact has been striking: nearly 96 percent of participants report a boost in confidence, a crucial shift during such a formative stage of life.

This room is where the magic happens. Yolande started a sewing program at Art Place because she “loves to make fun joyful stuff in a non-traditional way.” She taught kids and adults alike how to sew, and along the way shared her love of quilting.

At the end of the first quilting workshop, she asked everyone to write a reflection about their quilt and what it symbolized to them. They could write one sentence, or a paragraph or a whole page. The responses were powerful, insightful and remarkable-- one of the students wrote that her quilt made her feel like home. A 12 year old student wrote, "It reminds me of my great grandma." A Pennsylvanian transplant who made an improvisational quilt said “I thought I was going to use math and make a traditional quilt, instead Yolande asked me to make poetry”.

One year, she launched Project Runway—free sewing workshops that culminated in students designing and modeling their own clothing at a community-wide celebration. The program grew quickly: nine students the first year, eighteen the next, and by the third year, seventy-four kids were strutting down the runway. The graduations became big, can’t-miss events. One unforgettable moment came when a 14-year-old named Marlin debuted a West African–inspired jacket. At the end of the runway, he flipped the jacket open, dropped into the splits, and leapt back up to cheers. The crowd went wild—and not long after, Marlin launched a small business of his own.

But the real magic happens in the hours spent sewing together. In the afterschool classes, kids trade phone numbers, catch up, and miss each other when they’re apart. One year was especially hard, marked by a rash of school shootings. Yolande remembered it this way:

‘We make things, we work side by side, we laugh, and I let them just be kids. Once they settle into sewing, they love to sit and gossip and chat—it’s so sweet. But they also bring their problems, and we work through those too. That year, a 12-year-old boy was shot, and the kids in my class were his best friends. They came to sewing heartbroken, traumatized. So we talked about it, they talked with each other, and they said what they needed to say. And then, when they were ready—they sewed.’